VOCAL-Ease.html

Vocal-Ease

newly

revised - 2022

Foreword

• There are two reasons for studying vocal technique. The first is to

correct a problem which inhibits or restricts a singer's performance. The

second is to add new dimensions to an already workable technique. In either

case, a teacher is necessary. The purpose of this material is to acquaint

you with certain aspects of vocal technique which will be helpful when you

go looking for your first voice teacher, or for a new one.

Our world is very diversified, and it is often a problem selecting a teacher

who will be right for you. Styles in today's music differ so radically, that

a voice teacher must have an extremely flexible approach or method. Some

teachers lack this freedom or flexibility. If you have some basic knowledge

of vocal techniques yourself, you will be able to locate a teacher who will

benefit you.

Imitation ( copying sounds and styles of other singers ) is extremely

important, but there is no substitute for a good teacher.

The information on my website

https://dennisparnell.net/dp

- these are mp3 recordings of a piano playing a number of basic vocal

exercises

This booklet is provided only as an aid, to arouse your curiosity, and to

expand your knowledge. It is almost impossible to learn to sing correctly

without feedback from a knowledgeable teacher and many hours of diligent

practice. Armed with this knowledge, you will be able to find that special

teacher or coach and begin your studies with enough basic information to

avoid confusion.

Introduction

•For years, singing teachers have shrouded themselves and their

techniques with a certain mystique. Today, this situation is changing, but

it still exists to some extent. There is really no mystery where good

singing is concerned. Poor singing is usually due to incomplete knowledge. A

good teacher can guide a student toward more complete knowledge through

example and intelligent application of exercise. A voice teacher is usually

contracted via personal recommendation. Some voice teachers advertise;

other's don't. Word of mouth is usually excellent advertising, but the

teacher's best ads are his pupils. If it is possible to hear a number of

singers who study with the same teacher, you can usually make a good

evaluation of the teacher's ability. There are many different methods of

teaching vocal technique. Some of these techniques work for some people;

some do not. Knowing what you, the singer, need or desire to learn will make

finding the right teacher much easier.

For instance, if you are a pop singer, you may not want to learn operatic

arias. A flexible teacher will not impose upon you, requiring you to learn

things you don't need or wish to use. But a good teacher will give you the

tools necessary to sing any kind of music with the proper style and/or

sound.

There are many "singing teachers" who are often only

pianists. They can "coach" you to sing with the correct style, but are often

not equipped to help you solve problems of a purely vocal nature. (There are

coaches who may know as much or more about vocal technique as some of the

so-called voice teachers, however.) Teachers of vocal technique need not be

fantastic singers either, but they can usually demonstrate the techniques

they teach. Those who cannot leave themselves open to question. Often, there

is a simple or sincere answer: "Well my dear, I just turned ninety-five, and

I'm not quite up to singing those high C's anymore," or, "I never could sing

that note well, but I've taught it successfully to everyone of my pupils.

I'll have one of them show you how it should sound."

Be wary of the teacher who has had to stop singing because of vocal nodules

or similar problems caused by singing. This teacher certainly wasn't doing

it right himself, and may still be passing on information which could be

harmful.

Perhaps the best way to "check out" a teacher is to shop around. Audition

teachers. Listen to several of them before coming to a decision. Ask to

audit four or five of the teacher's lessons. As you observe, ask yourself if

questions are being answered in language you can understand, or does the

teacher use vague terms or foreign languages you don't understand? Are the

students all advanced, or are there beginners as well? Do they all make a

similar sound? Do you notice similar techniques working for the beginners as

well as the advanced? Is the teacher putting on a show for you? Do you mind?

Does the student taking a lesson mind? Does the teacher use the same formula

for all students or are exercises and music tailored for each individual?

Can you learn from this person?

The most important information you need is how your voice works. There are

many fine books available in the library which describe the mechanics of

vocalism in detail. At the end of this booklet, you will find a short list

of books and articles you may find helpful when you need more precise

information. You should also be familiar with the rather confusing

multi-lingual terms which make up the jargon of singers and singing

teachers: "on the breath," "support," "singing with the diaphragm," "pure

vowels," "head voice," "chest voice," "legato," "falsetto," etc.

At the end of this booklet, we will define some of these

terms. If more complete definitions are needed, there are several books

which have extensive chapters on definitions: these will also be listed at

the end.

In the past, where singing is concerned, science has often confused issues

more than clarified them. However, recent scientific investigation is

proving more helpful to the singer. MRI studies, new tools such as the

flexible laryngoscope, computer and analog studies are leading to some more

logical postulations concerning vocal registers and other factors unique to

singing. Still, voice production remains a highly subjective matter. As

such, there are many differing approaches and techniques which seem to work,

and until science can say with finality "this is how it is done," we sill

have to be satisfied with these empirical approaches and subjective

techniques.

Without knowledge and operational techniques, the act of

singing will still be somewhat of a mystery, but for anyone who wishes to

invest time, find a good teacher, and diligently practice, the mystery will

become less puzzling and more rewarding every day. The following sections,

hopefully, will add to your present knowledge and begin to give you some

concrete information about some of the processes in singing.

Vocal Cords (or Vocal Bands)

•Your vocal cords (also called vocal bands or vocal folds) are highly

elastic pearly-white membranes in your Adam's apple (properly called the

larynx). They contain many muscle fibers, which, like all muscles, can be

contracted or relaxed. They are consciously controlled, and may work

individually or together, as a single unit, or as separate units (somewhat

like the muscles in your tongue - which can "flatten out," "bunch up,"

"thicken," or "thin," etc.) Besides making sound, your vocal cords serve

another purpose. They act as a valve that keeps foreign substances from

entering your lungs. (Hiccuping activates the vocal chords in this

function.)

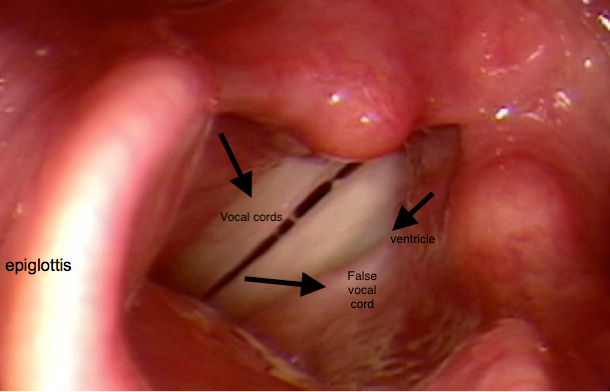

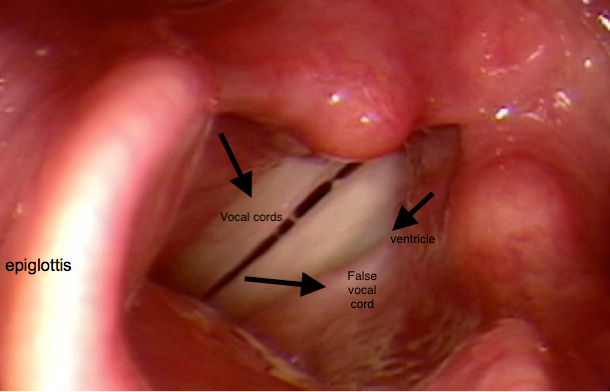

Also located in the larynx are the "false" vocal cords)

The space between the vocal cords and the false cords is

called the ventricle. The diagram will show you the vocal cords, the

ventricle, and the false cords.

This system is a double valve protection for your lungs. The false cords add

enough muscle to help you expel mucus on other foreign substances from the

windpipe. We do this when coughing. Since we can't open the necks of great

singers to watch their muscle coordination while they are singing, there is

still much conjecture about singing technique as it applies to muscular

functions. It is certainly safe to assume that control and coordination of

certain groups of opposing muscle systems, as well as good control of the

muscles, or groups of muscle fibers within each vocal chord, are necessary

prerequisites for good singing over several octaves without "breaks."

Many beginners or singers with inadequate techniques have

not discovered how to isolate certain groups of muscles from one another as

they practice. In some people, some of these groups of muscles are weak;

other people have other muscle weaknesses. Usually, we get years of vocal

practice, speaking within a rather limited range of musical notes (usually

in the "chest" or lower register) before we ever decide to become singers.

Muscle coordination in the speaking area is usually good,

allowing for a large dynamic range. However, in order to increase the muscle

range of the singing instrument, muscle must both be flexible and strong

enough to withstand the added air pressure of loud singing as well as the

rigors of extra stretching necessary to reach the high notes with an

acceptable sound (timbre).

It is the coordinated effort of both strength and flexibility that makes a

good singer. Our vocal cords are extraordinary instruments, but there are no

absolute rules about how they work; that is, there are so many minute

muscular variations possible, we must assume there are as many singing

techniques.

They work -- and they don't.

It was precisely this reason which led to the creation of this work,

"Vocal-Ease". Certain exercises can be used to add range and flexibility.

Others tend to be useful to build strength. Over-doing one type of exercise

can lead to an imbalance.

Good teachers usually let you know the purpose of the

exercises you are doing. Many exercises do not sound good or "correct," but

it is usually necessary to stumble through new muscle processes before

reaching a state of coordination, which sounds better.

There also exercises that address themselves to specific

problems such as too much air pressure, limited range, limited air pressure,

"breaks," etc. Some of these types of exercises sound horrible at first.

Usually, these are exercises that add brightness to an otherwise dull

sounding tone. They are often "high larynx" exercises (The "Jerry Lewis"

voice). Your neighbors won't appreciate these, especially late at night. The

purpose of these exercises is to help isolate and strengthen the weaker

range of your voice, which usually occurs above the highest "normal" speech

inflections. These exercises are especially helpful to female pop singers

who must sing in the middle and lower registers, or range, and to male

singers who wish to cultivate an easier production of high notes. The

exercises also help connect registers by changing the air pressure/vocal

cord ratio.

WARNING: Many teachers are not familiar with these exercises, and have been

taught that singing with a high larynx is not good (or even dangerous).

This would certainly be true where songs and arias are

concerned, but not as a training exercise to isolate certain sets of

muscles. The problem with the exercises is that they create a constricted

vocal tract - on purpose. There is a good reason for allowing this to

happen. Recent scientific data confirms that the larynx that doesn't

appreciably move while singing is generally not bothered by problems of

registration. This does not mean that there should be rigidity in the vocal

tract, rather only the most minimal movement of the larynx.

We do not under any circumstance, recommend singing with

a high larynx, except in certain styles or circumstances such as a

"character voice." We do recommend utilizing a tool which will allow the

singer to experience singing scale passages and melodies with little or no

movement in the larynx. This is often of great value to "belters," or

singers who have never experienced singing with a mixture in their higher

range. As coordination improves, the sound may be mellowed and the larynx

lowered into it's normal singing position. These exercises are also used to

add intensity to the "pure " falsetto, allowing it to "mix" with the notes

of the lower register.

The theory is that the vocal cords are allowed to be

pulled closer or held together more tightly with the help of several groups

of constricting muscles (the inferior constrictor ( one of the "swallowing"

muscles ), lateral crico-arytenoid, transverse arytenoid, posterior

crico-arytenoid). This, in turn, allows the vocal cord to vibrate over its

full length in a range which would normally have to be sung as falsetto with

some portion of the vocal cord not participating in the vibration, or the

cord not completely closing, creating a breathy tone. Ventriloquists have

used this brassy sound for hundreds of years, with few vocal problems.

1. Dr. J. Large: Vocal Symposium; Victor Fields article

2. Venard: Technic Book; Dr. Hans von Leden: Conversation, 1981

The Larynx

Larynx

muscles

(click on the above - a diagram on line of the larynx and its

surrounding muscles and cartilages)

•If you look at a diagram of the "larynx", you will see a

cartilage at the top of the windpipe called the cricoid, or ring cartilage.

Attached to the rear of the cricoid cartilage are two other cartilages which

function like levers, called the arytenoid cartilages. Functionally; the

arytenoid cartilages and their associated muscles pull the vocal cords

together for phonation, and pull them apart and away from each other so that

a person can inhale. The Adam's apple, called the thyroid cartilage, fits

over and around the cricoid cartilage. It is attached to the cricoid by two

somewhat loose joints, which allow the thyroid to "slip" or rock forward and

down when pulled by the appropriate muscles (sterno-thyroid). Your vocal

cords are also attached to the front part of the thyroid cartilage. When the

sterno-thyroid muscle contracts, it pulls the thyroid cartilage forward and

down, causing your vocal cords to be stretched, tightened and "thinned"

(much like the stretching or elongation of your bicep when you extend your

arm).

The elongation and thinning of the vocal cords is of the extreme importance

if you are a singer. To demonstrate the lowering and tilting action, place

your index finger at the top of your Adam's apple and yawn. At the beginning

of the yawn, you will probably feel your larynx being pulled down (and

perhaps forward). Normally, at the end of the yawn, most people feel some

rigidity above the Adam's apple. This is usually caused by some of the

powerful tongue muscles, which, unfortunately, are able to push the larynx

down from above.

Many singers utilize this technique to darken or "cover" their tones. If

overdone, this technique can be detrimental; it indicates that too much air

pressure is forcing the larynx up and the muscles which pull the larynx down

can not handle the load. Eventually, the use of too much reinforcement with

the tongue muscle can lead to a wobble, or a straight vibrato-less tone. (A

little reinforcement for a very loud note is all right, as long as it

doesn't become the rule.

In the long run, it is better to strengthen the pulling muscles - they will

indicate when there is an overload because the singer's vibrato will most

likely slow down.

These downward pulling muscles can be activated (other than by yawning) by

imitating a phony sounding "attention-getting" little cough. If you put your

thumb and index finger on either side of your Adam's apple and imitate this

gentle coughing activity, you will notice that your larynx has been pulled

down (as with yawning) but it stays anchored in the low position while you

are creating air pressure underneath the vocal chords by coughing. Coughing

itself is a rather violent activity for the vocal cords, so this must be

done gently.

If you begin speaking immediately after this light coughing exercise, your

larynx will probably rise immediately. This is simply habit. Try keeping the

larynx anchored in its lower position while singing or speaking a few notes.

The result will most likely sound low, hollow, and breathy. This is caused

by stretching the vocal cords. Since you have stretched them, it is also

more difficult to make them flex at the same time (much as it is difficult,

at first, to flex your bicep when your arm is fully extended.)

It is the coordination of both of these activities which most teachers try

to accomplish - flexing and stretching at the same time - as this allows

less air pressure to be built up under the vocal cords (there is less

muscular mass in the stretched/flexed position muscle than in the

flexed-only muscle) and singing becomes "easier".

When a beginner first lowers his larynx, his reaction is usually negative,

or at least. "…With all due respect, sir, I can't sing like this." The

lowering of the larynx creates a hollow, rather moronic sound when overdone,

and the coordination usually takes a while to refine. This sound is hollow

and "low" sounding because the larynx has been pulled down, creating a

larger resonating chamber above it; the vocal cords have been stretched and

more air is uncontrollably passing by them.

Stretching the vocal cords in this manner is not common to many forms of

American English. Consequently, these exercises can be very frustrating, as

the larynx will tend to rise into a higher, more "normal" position of speech

at the beginning of an exercise or sung tone. Changing the muscle pattern

itself takes time and practice, and the hollow sound being produced is

rather strange feedback.

It is the feeling of vocal ease which accompanies these exercises which

should be considered feedback. The air flows more easily past the stretched

vocal cords than it would if the cords were in a flexed, thicker

configuration. Visualization of the bicep as a single vocal cord is helpful,

as this muscle, and the control of it, are familiar to us all. Transference

of this knowledge seems to help students apply the lowering of the larynx

more quickly, and the quicker that the excess air pressure is eliminated,

the better off a singer is.

Exercises which raise the larynx in a higher than normal speech position are

also useful in the elimination of excess air pressure. The sound produced is

not the useful feedback - it is the ease of singing notes outside the normal

range which makes these exercises effective tools. Just as the lowering of

the larynx creates (eventually) a more sonorous sound, the raising of the

larynx creates a more intense sound and can be of help in overcoming

breathiness.

The exercises, which change the timbre (quality) of the voice, are, or may

serve as "primaries" in learning vocal production. When singers become too

extravagant, tiring their voices, these exercises may also be used to

reestablish better muscle coordination, allowing the singer to sing more

easily again.

Breathing

•"Breathing is the secret of good singing." This is heard almost as

often as "Sing from the diaphragm!"

In a way, it is true that breathing is the secret of good singing, but what

exactly does that mean? Basically, it means how you breathe OUT. The control

of air pressure from your lungs against the vocal chords is the primary

"secret" of good singing, and all of us, with a little practice, can master

the coordination of breath control and singing tone. I quote here from the

book "Voice-Speech-Language Clinical Communicology : It's Physiology and

Pathology" by Richard Luchsinger and Godfrey E. Arnold

(page 149):

DIAPHRAGMATIC BREATHING: Once again the

widespread fallacy of speaking with, or from the diaphragm should be

mentioned here. As explained in the first chapter, the diaphragm is an

inspiratory muscle. During its inspiratory contraction, its dome-shaped

convexity is lowered. Through this pumping effect, air is drawn into the

lungs. Expiration is accomplished chiefly by contracting the external

abdominal muscles, which push the relaxed diaphragm upward during

expiration so that the lungs are compressed and emptied. It is good to

remember the following points. The diaphragm is inactive during

expiration, be it silent or phonic. Since it lacks proprioceptive

sensation (it is unaware of itself) the movements of the diaphragm cannot

be felt. Since it is extended horizontally between the lungs and the

intestines, the diaphragm cannot be seen from the outside. When the chest

goes up, the diaphragm is pushed up passively. It is nonsense when some

naive voice teacher proudly taps his inflated chest, proclaiming, "Look at

my strong diaphragm." Notice that the diaphragm contracts when you

inhale and relaxes when you exhale!!

Now, go find something heavy and lift it. (Piano, sofa, filled suitcase,

barbell, etc.) Be aware of two things as you lift: your throat and your

abdominal muscles. Put the object down for a moment. Did you continue to

breathe normally as you lifted the object? If so, you already have some

knowledge of breath control. If not, you probably tightened your body and

throat noticeably.

For good breath control, you must learn to let the vocal cords "sphincter"

or "muscle up" a bit, i.e. over-contracting, and closing your entire throat

as you contract your abdominal muscles. Then you must allow yourself to "let

loose" a little at a time, until the vocal cords are freely vibrating and

the air feels as though it is "Flowing" from the throat. Like switching when

rubbing the stomach and patting the head, this coordination may be difficult

to master at first, but after some practice, it will come easily.

To see just how naturally the abdominal muscles and the vocal tract work

together, have a friend hit you in the stomach. Not only do your stomach

(abdominal) muscles contract, but your throat shuts off as well. This is a

natural protective device to keep the internal organs from being injured.

Singers call this coordinated muscular synergy "support." Singing with too

much of this throat constriction (or "over-support") is a habit which must

be modified. There are several ways to decrease this sphincter-like action

in the throat. Go back to that heavy object and lift it again. This time,

talk to someone (or yourself) while lifting. If your throat feels tight,

talk with a more breathy tone, and if possible, try and make it not only

breathy, but slow dumb, and moronic sounding (lowered larynx). Sing a scale

while lifting the object. It takes a bit of practice to get used to feeling

the abdominal muscles in the state of contraction while you are using the

throat for unrestricted speaking or singing, and coordination may prove

troublesome at first, but the use of varying degrees of this abdominal

tightness (or tautness) will allow you to sing strongly and yet freely. Most

singers refer to this kind of abdominal muscle contraction as "support."

With abdominal muscles very tightened (as though someone were about to hit

you), sing an upward scale, somewhat softly. If your throat doesn't

"sphincter" shut, you will probably be able to sing slightly higher in your

"chest" or normal voice than you normally do. Why?

Because you have reduced the air pressure underneath the vocal cords.

Another effective way to accomplish this is to exhale almost all the air out

of your lungs, then try to sing that difficult phrase with the high notes.

(Or just the high note alone) The higher notes will often prove to be

easier. Excess air pressure is the primary enemy of good singing.

Sometimes, a singer is so used to excess air pressure that it is difficult

to convince him that he is making enough sound when a normal, healthy

balance is reached. Tape recorders are very helpful in these cases. If you

are a person who sings loud and has a limited range, you probably are using

too much air pressure. Usually a combination of exercises using tightened

abdominal muscles (support) and the raucous sounding high larynx exercises

bring the quickest relief. Adding breathiness also works to some extent.

High larynx exercises are useful here because the larynx is already being

pushed up by too much air pressure from underneath the vocal cords, many

unnecessary muscles are contracting, constricting the vocal tract, so the

singer might as well rest the larynx on the bone at the base of the tongue

(hyoid bone). Since the larynx cannot rise any further, the constricted

unnecessary muscles usually relax, and higher notes can be reached more

easily. Usually, a great deal of relief is experienced by "belters" and

shouters when the larynx is allowed to rise and the sound allowed to rise

and the sound allowed to radically " thin out." There is still plenty of

volume, but the singer cannot believe that the raucous sound being made

could be of any use or help at all. The usual reaction is "Are you kidding?"

For people who tend to abuse their voices, any way of relieving excess air

pressure is a beginning. Once air pressure is reduced, exercises to lower

the larynx and improve the quality of the sound can be introduced. We'll

explore that in class.

Air pressure can be changed in two ways: either by changing tension in the

vocal cords themselves (as in the lowered larynx exercises already

discusses) or with the exercises which change the vocal cord/abdominal

muscle coordination. An effective demonstration of abdominal muscle

contraction and the resulting change of breath pressure against the vocal

cords is to sing arpeggio or scale passage up to a high note, quickly

bending over from the waist just before reaching the high pitch. This will

often "free" a constricted throat by a sudden change in air pressure, and

the high note will be produced more easily.

To further increase your understanding of this process, take a big breath,

hold it in your lungs with your vocal chords, and now attempt to talk

without allowing any breath to escape (obviously, some breath must be used).

Take another breath. Tighten your abdominal muscles and keep them extra

tight now open your throat as though you were going to yawn. Don't yawn, but

speak quietly. If you have succeeded, and the speaking tone is mellow and

soft and does not feel constricted in your throat, you are using the

singer's breath control ("support"). Try singing a scale, tightening the

abdominal muscles as you sing higher. You will learn through practice just

how much contraction is needed to help you. Too much rigidity is just as bad

as too little. Contraction of the abdominal muscles changes the flow of air

because it restricts the action of the muscles, which cause the diaphragm to

push the air out of the lungs.

If you fill a balloon half full of water, hold it with one hand at its

opening, and use the other hand to squeeze the lower half of the balloon.

The water will be quickly displaced into the upper portion of the balloon as

your hand comes together in a fist. The squeezing is no problem and the

water offers minimal resistance. It is much the same with the air in your

lungs when you sing. The vocal cords, if working properly, do not offer a

lot of resistance to the air flowing by them. It is very easy to use too

much air pressure without even knowing if there is a problem. The only

indication to the singer is usually an inability to sing high pitches using

"full" voice. The vocal cords cannot stretch enough to make the higher

pitches because too much air is pushing against them, and rather than fight

a steady stream of highly compressed air, the vocal cords simply release

some of the bundles of muscle fiber used to make pitch. The voice breaks;

the pitch goes somewhat sharp and is tuned back down to the correct pitch,

but now in "falsetto" or "head voice." (Like leaning into a strong wind,

only to fall down as the wind suddenly stops blowing.)

As a rule, when a singer attempts to sing a high note with too much air

pressure, the voice simply cracks and breaks into another register. The

singer must learn to either decrease the flow of air from his lungs or

change the air compression above the vocal cords in order to create a

favorable acoustical situation, which helps to decrease the pressure under

the cords. Back to our water-filled balloon if you stiffen the muscles in

the squeezing hand, you will notice that you cannot squeeze as fast. As a

matter of fact, you can actually control the speed of the squeezing by the

corresponding amount of muscular rigidity in your hand. By tightening the

abdominal muscles, you may control the amount of air being pushed out of

your lungs. This takes practice, but the resulting control is invaluable to

all singers. By imposing this exterior tension, you generally reduce the

amount of unnecessary muscle tension at the vocal cord level and at the

larynx. Since the abdominal muscles are much larger and stronger than the

muscles of the larynx and throat, restricting their activities (abdominal

muscles) will allow the smaller muscles of the vocal tract to carry on with

greater efficiency. This allows you to sing better, using exact

predetermined amounts of air pressure and vocal cord tension.

A change in the flow of air beneath the vocal cords will allow more

flexibility and vocal color, but this technique of abdominal support is

always "guess work." There are also exercises to change the flow of air

above the vocal cords. These are most helpful in dealing with severe breaks

or register shifts in the voice. These are discussed later with the

explanations of the exercises on line. These are the real creators of

"support," which is a result of proper air compression above and below the

cords.

Ratios

•A garden hose with the common, twisting nozzle might be

used as an analogy to the vocal tract. The faucet where you turn on the

water corresponds to your abdominal muscles, the water to the air in your

lungs, the hose to the vocal tract, and the nozzle to the vocal cords. If

the nozzle is opened all the way, a thick stream of water results. (The

analogous sound is the lowered larynx sound.) If there is too much water

pressure, and the hose is not reinforced, it is liable to pop or spring a

leak. The vocal cords are able to take only so much pressure before they

"crack" or pop. Voices, just the same as different brands of hoses, are

built to withstand differing amounts of pressure. Some singer's muscles

allow them the luxury of singing very loudly and heavily. Other singers have

lightweight instruments. Each singer must be aware of his/her physical

limitations. The ratios can be changed, but only within the singer's own

physical parameters. Much like the garden hose, you can either make a more

efficient spray at the nozzle, or you can add water pressure and leave the

nozzle the same, or you can walk close to the object being sprayed or any

combination of the above. Singing is very much the same. There are infinite

variations and combinations open to the singer and teacher: if one way

doesn't work, try another. As you learn to balance your instrument, singing

with the most effective air/muscle ratio, you can begin to add weight (air

pressure) as your muscles become stronger. Just as a weight lifter learns to

lift more and more, the singer can add a certain amount of depth and volume

to the sound of his voice as the years go by. Unfortunately, many singers

don't take the time to establish this fine-tuned balance before they go out

to perform. A few years or tours later, they wonder why they are having

vocal problems. A singer's voice should continue to sound free (and perhaps

better) as he grows older. Singers who risk using too much air pressure too

often pay a heavy price, and singers of rock music have to be especially

careful, as the styles of music they sing often demand vocal production

which is less than ideal. Singing with the improper ratio of air/muscle is

usually easy to identify. High notes sound or feel like shouting or yelling.

The larynx is usually being forced upward or held rigidly downward. Veins in

the neck protrude. The top range is usually limited. Breaks in registers

occur. Faces get red. Hoarseness occurs. Eventually, a raspiness or extra,

non-musical sound appears in the voice (Janis Joplin, Joe Cocker, Axel Rose,

etc). If technical problems are not corrected at this point (it is sometimes

already too late), permanent damage can result in some form of contact

ulcers or vocal nodules.

video

about vibrato

another

video about vibrato (Rodger Love)

another

video about vibrato

one

more (Justin Stoney)

correction about Justin Stoney's use of the word

Hertz (Hz) - hertz is a measure of a pitch - oscillation would have been

better to describe the sound of the slight "wobbling" of vibrato

• In order to sing both loudly and freely, singers

rely on the oscillation of tone, which we call vibrato. This is an

up-and-down movement of pitch; the top being the actual pitch and the

oscillation is to a semitone (half step) below. A vibrato usually pulses

between five and seven times per second. Slower than five pulses is called a

wobble. Faster than seven is referred to as a tremolo. Some people "have"

vibrato naturally; others do not and must cultivate it. Different styles of

music demand slightly different uses of vibrato technique. Operatic style

requires a steady vibrato between six and seven pulses per second. A steady

oscillating tone is the ideal. The steadier the oscillation, the more

pleasing it is. Straight tones are usually made for artistic effects, if at

all.

Vibrato for musical theatre varies from singer to singer.

A straight tone is usually acceptable at the beginning of a sustained tone

as long as it begins to vibrate within a short time. Pop music is full of

straight tones. Words are more important than tonal production.

Pop singers often cultivate (or attempt to

cultivate) a straight, vibrato-less tonal production as part of their

"style." Needless to say, there are few pop singers who sing straight tones

all the time --- no one would be able to listen for too long. Almost all pop

singers use some sort of vibrato or oscillation in their sustained tones.

Using vibrato allows the singer to adjust a slightly out-of-tune sustained

note without the listener being aware of the adjustment Straight tones must

be sung in tune. The oscillation of the vibrato makes "in tune" a rather

flexible concept. Another reason for the use of vibrato is simply muscular

freedom. Sustained muscle contraction is very difficult: a slight

oscillating movement is easier and the sound is esthetically more pleasing

in our Western culture. If you are a singer who does not have a vibrato, but

wishes to cultivate one, the easiest way to begin is with a wobble (a very

slow up-and-down movement from pitch to pitch). Having a metronome helps

because you can check your progress accurately. If your throat is too tight

or restricted, you will find the vibrato difficult to execute at first. If

this is the case, then a very wide pitch wobble (like yodeling) often helps

get rid of the constriction. This exercise should also be practiced wobbling

the voice one whole tone above the desired pitch. This is extremely helpful

in mending register breaks. It sometimes takes months before oscillation

being practiced begins to seem natural and the vibrato works "by itself."

Learning a vibrato takes practice and more practice. Once in a while, a

singer will constrict his throat so strongly that even the wide wobbling of

a pitch will not make a satisfactory vibrating sound. In this case, get your

friend again, have him make a fist, place it on your abdomen and while you

sing a tone, pump the fist gently in and out. If your abdominal muscles are

not too tense, the rapid change in air pressure against the vibrating vocal

cords will create a "vibrato" of sorts, and although the vocal tract may

still be somewhat rigid, at least it will cause the singer to be aware that

a vibrato can be done. After a while, singers with problems like these,

usually loosen up enough to begin the pitch wobble.

The eleven "Standard

American Vowels"

Video of 11

Standard American Vowels

The

Circle of Vowels - diagram

• The purpose of this chart is to show reasons for

beginning some exercises with certain vowels. If you say the word "WAH" and

extend it until it sounds like "OOOWAH," you will notice that your lips are

making a smaller opening on the vowel "OO." The closer you got to "AH," the

farther your lips open (and perhaps your jaw as well). Many novice singers

are unaware that slight air compression (or pressure) differences occur

while singing: these are caused by the changes in the opening and closing of

the lips and the raising and lowering of the tongue and soft palette inside

the mouth. Untrained singers usually sing as though the bigger the opening;

the more volume is needed---somehow trying to fill up the additional space

with more sound. This causes uneven singing, some vowels being sung louder

than others. This is hard, not only on the singer's voice, but on the

listener's ear as well. Listeners respond to predictable changes in sound

levels. Changes which cannot be anticipated cause confusion (or surprise).

In music, we tend to respond to "normal" sequential sounds (we can

"understand" them) of similar sound pressures. Usually, when a listener is

subjected to random changes in sound pressure levels, he cannot predict the

next sound or "follow" it, and generally loses interest. In singing, this is

often referred to as singing "without line." Exercises to line up the

sound-pressure levels of different vowels may be begun on any vowel. Each

teacher or "school" seems to have a favorite pattern for this kind of

equalizing exercise and there is much disagreement about which method is

best. There is, however, no disagreement about singing with a "good line."

The IPA - International Phonetics Alphabet

Mixing or Covering

•An entire work dealing with this subject is

possible. The term "covering" is used by most vocal teachers to mean some

sort of change in vowel quality as (or before) a register change takes

place. It seems that if the larynx stays put while singing (not rising with

the pitch), "covering" or mixing takes place naturally, and there is not too

noticeable a change in the quality of the tone. Many Americans do not seem

to "cover" naturally. Perhaps this is because we are taught to speak quietly

and yell loudly. Reverse this process-yell softly and speak somewhat louder,

and the singing voice in its full range becomes available. If it were only

so easy! Most untrained ears will tell you that a "covered" vowel is

different than an "open" or normal, speech-quality vowel. Perhaps it is

easiest to say that a "covered" vowel is a vowel that has been slightly

modified in its harmonic content in order to avoid phase cancellation (or, a

break in register). There is definitely a subjective recognition of this

mixing or covering process and each singer tends to cover at a slightly

different points or pitches. Almost every voice has the ability to sing in a

heavy register (usually called "chest voice") and a lighter register

(sometimes called falsetto, sometimes called "head voice"). It is our

opinion that every voice should be taught to mix these two slightly

different voice qualities into a "purple zone." If the heavy register is

thought of as red, and the lighter register thought of as blue, there is

always the possibility of a purple zone. The diagrams will show more than

long verbal descriptions, but a few words of interest might be noted: Some

teachers treat registration as though it didn't exist, i.e., the entire

voice is a purple zone. This is fine if it works for you, but,

unfortunately, American voices do not always respond to this single register

approach. A single register voice is the ideal. We are usually satisfied

with a bit less, which is a red-and-blue voice with a large, moveable purple

zone. For example, certain areas of this voice may be sung with varying

degrees of red/blue ratios, or all red, or all blue. This kind of singing is

usually full of interesting color changes and tonal surprises which may be

calculated, artistic choices of the singer. All red or all blue voices are

possibilities, but their ranges are by necessity limited. The general rule

is that a well-mixed instrument sings better and will last longer, although

there are many exceptions to the rule. Covering, or the lack of it, is

(or should be) at the discretion of the singer. More information related to

this process will be found in the next chapter and tape on "style."

STYLE --- MAGIC TRICKS OF

SOUND

Singing is a unique process; it is two things which usually happen at the

same time: words and musical pitches, or musical pitches and words. Over the

years, reversals of these two priorities have caused a lot of confusion.

Natural or

Learned

• Some singers learn to sing as though it were an entirely

musical process, and they are successful. Others do not need to "learn"

singing. They seem to have a natural gift, and they are successful. The

success of either approach is possible because singing is a process, which

incorporates both music and speech. A process is a series of continuous

actions, which brings about a desired result. Since the series of actions is

continuous, one may begin a process at almost any given point, provided it

is completed (covering all bases and reaching the starting point again).

This is the primary reason there are so many different singing techniques.

Many of these techniques begin at different points, but if the teacher is a

good one, most of the bases will be covered. The only necessary prerequisite

for singing is speech. If one is musical, so much the better. Unless there

are speech defects or a regional dialect, which must be changed, speaking

itself is not usually considered a technique except by actors. Most people

think of speech as a natural process. However, it had to be learned in

childhood, so it actually is a learned activity or "technique." Keeping in

mind that singing is both speech and music, singing techniques can be

learned either as music or as an extension of speech.

Music Imitates Speech

• More often than not, musical phrases we sing imitate

natural speech inflections. Good song writers almost always compose pieces

which seem to "sing themselves." Some singing teachers appear in many cases

to be unaware of this "music of speech." To them, isolated notes and the

music itself become more important than the flow of words. Learning to sing

using speech inflections is not the most common approach of today's singing

teachers. However, many fine musical coaches use this technique to great

advantage. The use of speech inflections adds another effective tool for

improving range, eliminating register breaks, and singing smoothly (legato).

We are not usually conscious of actual musical pitches when we speak. This

is because normal speech is inflected words flow naturally into other words,

sentences into sentences. Our voices rise and fall according to our moods.

We speak loudly or softly, but, most of all, we speak smoothly. We do not

jump directly from one pitch to another. We slide through pitches, unaware

of the pitches themselves as separate entities. Thus we use the vocal

instrument in a learned but seemingly spontaneous act-speech. It is a vocal

teacher's task to help the singer make music sound as spontaneous as natural

speech patterns. Many singing teachers and choir directors encourage pupils

to sing from one pitch to another with absolute accuracy, as though each

pitch were disassociated from the next. This is counter-productive for an

aspiring soloist or "lead" singer because it inhibits natural speech

inflections inherent in the music. (This is one reason solo voices tend to

stick out in a choir.)

Magic Tricks

• A good singer must learn many tricks. The most

important is timing. Timing is responsible for the singer's style. Singers

who sound "sloppy" have not learned the tricks of singing legato (Italian

for "smooth"). Like the choir singer, the choppy sounding singer attempts to

sing accurately from note to note. This would be highly commendable if we

only sang vocal exercises. However, the singer must sing words and convey

emotions. That means dealing with problems caused by the interruption of

vowel sounds with consonants (both voiced: with sound-the, zoo, view; and

unvoiced: without vocal sound - p, t, s, ch, f, etc.). Singers sound choppy

because they are singing digitally (much like an artist presenting a drawing

composed of unrelated dots with no lines joining them).

To our ears, singing is more holistic; an analog process - not a digital

one. Vocal cord vibrations themselves are digital, but our ears cannot

process the information fast enough to hear the separate vibrations (or

cycles). Singing must use some sort of speech inflections to sound natural.

Digital speech can be heard in the toy "Speak and Spell" or other computers.

It is mechanical and does not flow naturally.

Singers whose voices sound naturally are like

magicians; they have learned sleight-of-hand tricks with their voices which

disguise the movements from note to note. These movements will then be

unnoticeable to listener. Legato singing is really an illusion using several

techniques, especially vibrato.

We cannot see the individual frames of a motion

picture-they go by too quickly. We see only the motion, or what appears to

be motion. If the speed of the projector is decreased, there comes a point

where one can discern individual frames. Computer programs such as Voce

Vista are allowing us to see this in action as of 2020 and later. A singer's

vibrato operates much in the same manner. Vibrato helps mask or smooth out

the movement from one pitch to another. It also helps the singer maintain

muscular freedom and decreases the possibility of rigidity in the vocal

tract. A vibrato of 4 pulses per second is audible to most people as two

separate notes. This is called a wobble. At about 4 1/4 pulses per second,

we begin to hear what appears to be a single, oscillating note with vibrato.

Generally, a vibrato between five and seven pulses per second is acceptable

in any style of music. Anything faster than seven pulses per second is often

considered annoying, though some singers have been very successful with this

type of sound (called tremolo). This tremolo is found in many French singers

and some "country" singers. Smoothing out the movement from one pitch to

another higher pitch is desirable. It is difficult for a beginner. The

difficulty is due to the interruption of vowel sound by consonants.

WHEN ANY UNVOICED CONSONANT OCCURS ON A DOWNBEAT,

THE FOLLOWING VOWEL MUST ALWAYS BE LATE. Choir singers stay together by

singing consonants at the same time. Good soloists do not sing in this

manner since this does not permit them to "ebb and flow" naturally, leading

the accompanying instrument(s) or conductor in a well-defined musical

interpretation. When a vowel occurs after a downbeat (because it follows an

unvoiced consonant). There is no way anyone can predict exactly when the

vowel sound can begin. As a consequence, the singer's voice will always seem

to follow the accompanist or band (orchestra), rather than to lead it. No

subtleties can occur, as there is no musical give and take. This is where

the magic must take over.

To make the movement from one note upward to another

appear smooth, the singer learns to aim for a pitch slightly flatter

(usually between 1/2 tone and one whole tone) than the desired pitch, and

then tunes up. (We have confined the discussion to upward movements rather

than downward, as these are the more difficult of the two due to increased

air pressure and muscle tension of the higher pitch. Downward pitch shifts

usually "relax" more naturally.) Because of traditions, our ears accept

small degrees of this tuning. What we do not accept is a musical interval

which is unintentionally sung sharp and then tuned downward. This is always

the mark of an inexperienced singer. This downward tuning sounds unnatural

because it does not follow our speech inflections, which rise to a pitch-not

above it and back down. When the singer's vibrato occurs during the upward

tuning or immediately when the note becomes in tune, the singer has used the

classical or "legit" technique or style. The movement, from note to note,

sounds smooth to the listener. If there is no vibrato before the note is in

tune, the singer has used a pop-singing technique. It is important to

remember that we are speaking about a "gliding" movement, which takes only a

fraction of a second. If this gliding movement takes too long to execute, it

is called scooping. This is usually undesirable, especially in classical

music. If the slightly flattened tuning pitch is much lower than one whole

tone, the tuning begins to sound sloppy and artificial.

Opera singers generally strive to maintain a very

steady vibrato pattern of about six pulses per second at all times. A

totally predictable, beautiful tone is the ideal. Unfortunately, words are

often sacrificed for the tonal ideal, though it is not always necessary to

do so. Straight tones without vibrato become artistic devices used to convey

emotion. A slide upwards is sometimes called a portamento, (although this

has come to mean a longer, more pronounced linking of notes than we are

discussing here). The operatic (classical and/or legit) tuning upward almost

always begins slightly under the desired pitch. The vibrato begins before or

as the note becomes in tune. Vibrato has the effect of further disguising

the slight mis-tuning. For the "natural" singer, this mis-tuning is done

without much conscious effort (probably because it is just like speech). For

the less gifted, or the singer with only choir experience, this kind of

tuning can be difficult to achieve. Some teachers tell their students to

sing the consonant before the beat. For a novice, this is difficult because

it does not feel natural to sing ahead of or "outside" the beat. However,

that is the trick.

Sensitive conductors and musicians always make allowances

for these tunings. This is the nature of rubato (freedom in tempo). By

taking a bit longer to tune a note, the singer indicates a slight retard-not

a change of tempo. A slight increase in the speed of the phrase is indicated

by tuning the note more quickly. These subtleties take place in a fraction

of a second; yet accomplished musicians are always aware of these changes

and respond accordingly. Only the insensitive plow ahead, not waiting for

the colleague to tune. Since this tuning is subtle and happens so quickly,

the audience is only aware of the magical, spontaneous effect.

Singers who are able to maintain very steady vibrato patterns have another

possibility open to them when moving from note to note: they can make the

move within a single vibrato pulse. This type of tuning is extremely

accurate, musical and is a highly desirable technique to cultivate. It's

effect is not as dramatic as the slide but for coloratura singing or musical

passages which require speed and agility, this technique is often more

advantageous.

Singing technique for the musical theater requires

knowledge of some operatic technique as well as knowledge of some pop styles

and techniques. The legit singer has no real singing style of his own

anymore; it is something between pop and operatic styles. The more stylistic

techniques this singer knows, the better he or she will be prepared to enter

the musical theater. In many cases, legit singers need as much range as

opera singers do; the better he sings, the more opportunities in this field

will be open to him or her. Pop music requires a technique somewhat the

reverse of that used to sing opera. Tone production, although important, is

usually secondary to the words and their meanings. Consequently, vibrato is

often partially discarded so that the musical tones sound more like speech.

The pop tuning (or slide upward) often begins accurately either one

semi-tone or one full tone below the desired pitch. Pop tuning is not so

much a slide as it is an accurate mis-tuning. Sometimes this gives the

listener the impression that the singer has made a little cry or sob before

the note. Country

singers often employ this technique more conspicuously than singers of other

styles. Regional and/or ethnic speech patterns also play a large part in

determining the style of a singer. However, with the availability of

recorded music and what is becoming known as "crossovers" or "fusion" (from

one style into another), it is not uncommon to hear singers using styles

that are completely alien to their place of origin ("Rocky Raccoon" by the

Beatles, "Sail Away" by the Commodores, anything by Randy Newman, anything

by Charlie Pride, anything by Teresa Stich-Randall, etc.). Any style can be

learned and any "natural style" can be changed.

Although unaware of it in most cases, many

African-American singers make sounds similar to African ancestors. Many

African dialects are spoken with very strong, sub-vocalized consonant

sounds. These sounds pull the speaker's (singer's) larynx down low as they

are made. Besides this, certain African vowel sounds are produced with a

high larynx. As a consequence, there is a lot of laryngeal movement up and

down during singing. These African speech patterns have unwittingly

influenced generations of African-Americans, and the resulting styles of

singing often still reflect African laryngeal movements. Vowels in this

style usually follow the pattern of "hooty" oo and ee vowels produced with a

slightly lowered larynx and bright or brassy ah, uh, eh, ay, and aa (as in

cat) vowels produced with a high larynx. Vibrato in this style, more often

than nit, is slowed to four or five pulses per second, and the upward

tunings take longer than in other styles. The Country style of singing gets

many of its stylistic idiosyncrasies from Scottish and Irish ancestry.

Vibrato is usually cultivated. Tremolo is even acceptable. As a rule,

laryngeal position is high. The upward tunings are very accurate,

vibrato-less moves from the semi-tone or whole tone under the note up to the

desired pitch.

Jazz singers usually employ a more

instrumental approach to vocalism. Tone color, exact pitch and good

intonation as well as excellent rhythm are important. Musical expression and

the ability to improvise are also important. The jazz singer's tonal

production tends to differ from singer to singer-there is no specific jazz

sound. Rhythmic accuracy and vocal flexibility are the most important

attributes for the singer of jazz. There are certain types of commercial

and/or background music which require singing absolutely in tune. For this

reason, vibrato is not employed, and the music is sung in pop style. This

kind of ensemble singing is different from choir singing in that totally

uniform sound is expected. Any individual voice is subjugated; a perfect

blend is the expectation. This style is difficult and requires tremendous

concentration because fractional differences in tuning create problems.

Opera singers often sound out of tune when singing

in trios or quartets. They usually are. One cannot tune three or four

pitches oscillating at various speeds unless he either stops the

oscillations or puts them in phase. Most opera singers are too egotistical

about their own "technique" to do either of these things. Two out-of-phase

vibratos cannot be tuned accurately. Two or more vibratos which are in phase

create a peculiar, but interesting sound, frequently used by contemporary

choral composers and certain rock groups: Lygeti, Penderecki, Vanilla Fudge

and others. This "in phase" vibrato is basically used for effect.

Most small vocal groups opt for minimum or no vibrato in order to stay in

tune. Original or predetermined key signature is a problem facing the

classical and musical theater singer which does not often affect the pop

singer. When the pop singers uncomfortable with a piece of music in a

certain key; he simply changes it into something more comfortable. Usually

this is impossible in musicals or opera. The cost of transposing orchestral

parts alone is prohibitive, and many composers have a certain vocal sound in

mind when they write their music. A change of key would alter the sound the

composer wanted.

As a result, certain peculiar vowel qualities have become indispensable

by-products of having to sing in higher than normal speech ranges. This

applies especially to the high range of male operatic singers; they have

"operatic" or "covered" sound in their high ranges.

Bear in mind, the opera singer must still sing

UN-AMPLIFIED over a full orchestra in most cases. Consequently, opera

singers have developed a particular tonal quality which carries (or

projects) over the orchestra (or, more accurately, through the orchestral

texture). This kind of tone is said to have "ping," "buzz," "edge," "cut,"

etc. The more scientifically oriented, call the buzzing harmonics in this

tone "the singer's formant." It is a harmonic envelope of overtones between

2,800 and 3,300 cycles per second. There are few strong harmonics in the

orchestra texture to compete with the singer's formant in this area of

pitch, and even a singer with a relatively small voice, but a well-defined

singer's formant, can be heard through a large orchestra. Strangely enough,

this particular area of harmonics is also a strong resonance frequency of

our ear canals, so we tend to amplify the singer's formant within our own

heads, as well. This causes physical stimulation or excitement for the

listener. As orchestras and the places they played became larger,

accommodating larger audiences, it was the singers who developed these

ringing, resonant voices that survived the rigors or singing with (or

against) the larger orchestras. When electrical amplification was

introduced, the need to produce a ringing sound was left to the singers of

acoustic music (opera, concert, choral, musical theater before "Hair"), and

optimal singing (loudly but easily) was no longer necessary to be heard. One

simply cranked up the volume on the amplifier. New styles of singing quickly

became popular as they tended to sound more like "natural" speech than the

ringing operatic sound.

However, the singer's formant is till the

hallmark of healthy, well-produced voice. Combined with a good, controllable

vibrato pattern, a singer will have strength and flexibility in the same

instrument. (He will also stimulate our ear canals!) Many producers or

recording engineers (especially sound mixers on the road with rock bands)

turn down the 3,000-hertz area on their equalizers in order to "mellow out"

the sound of the vocalist. This can create problems for the vocalist who

cannot understand why he cannot hear his voice. In most cases, the singer's

formant or harmonic area in the 3,000-hertz area will be missing or have too

little amplitude. Boosting this area on the vocalist's monitor speakers will

keep him in better health and less likely to get "Vegas throat," nodules, or

other throat problems.

A singer with a ringing voice is fortunate. If the ringing is bothersome,

adding a little more breath or lowering the larynx slightly can modify the

tone. Good health and good singing techniques are necessary for vocal

longevity and a fulfilling career. The "magic tricks" of vocal style are

keys which will open the doors of artistry for any singer who wishes to

broaden his horizons and communicate with an audience.

Next Page