<b><font face="Faucets"><strong><u><font

face="georgia, times new roman,times"size="3">>

Faucets

Faucets

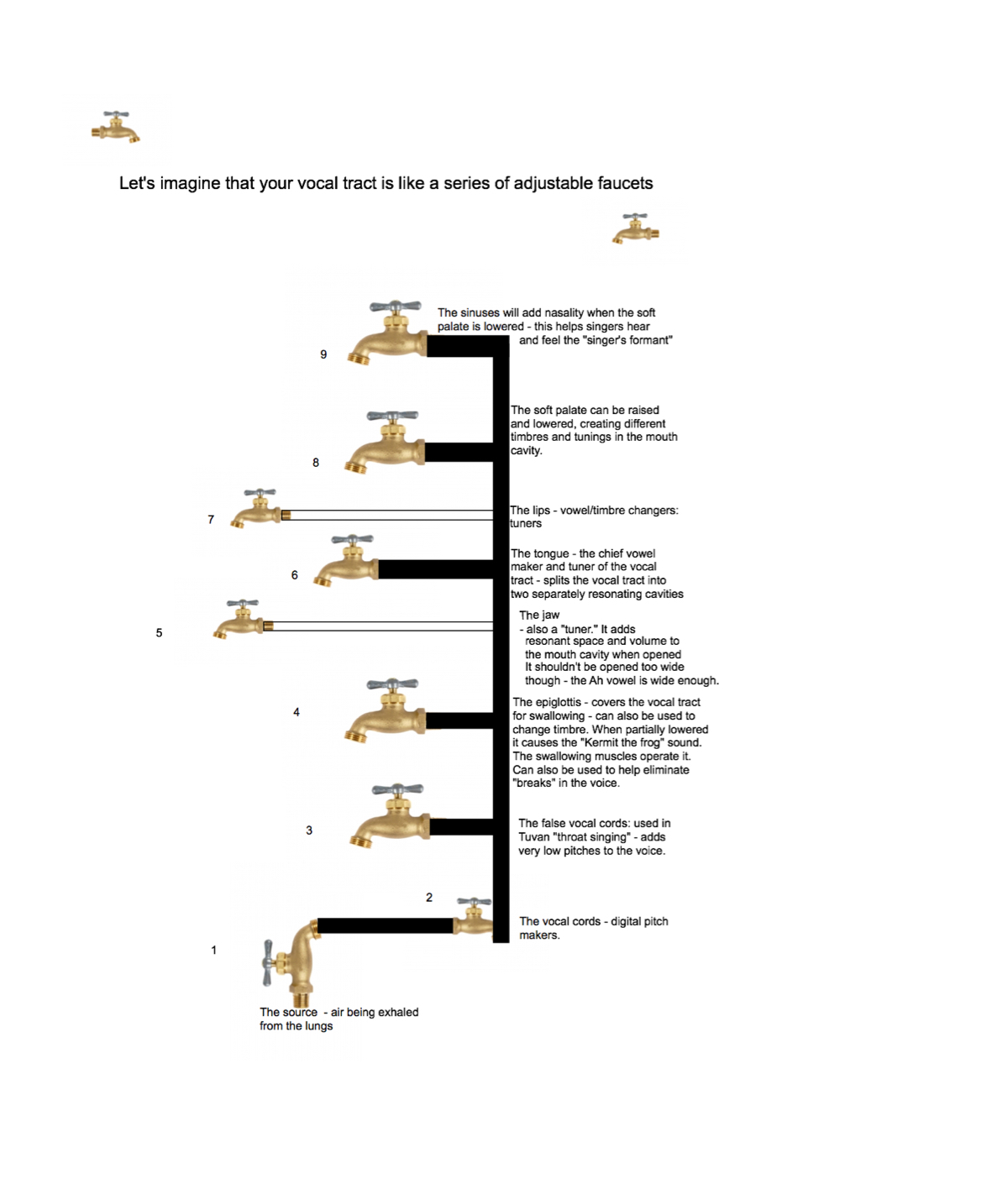

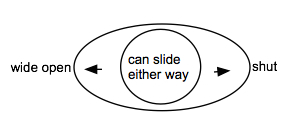

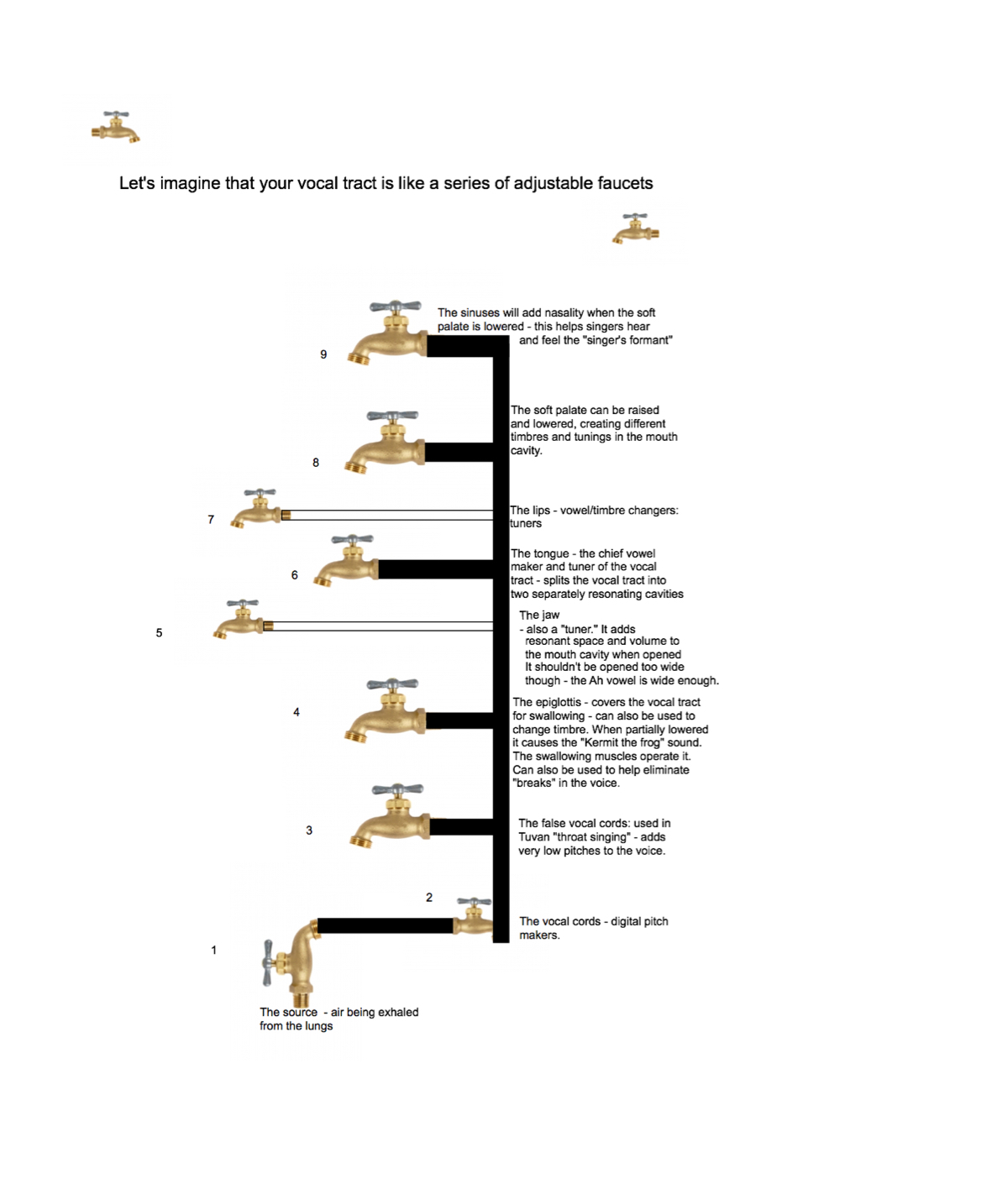

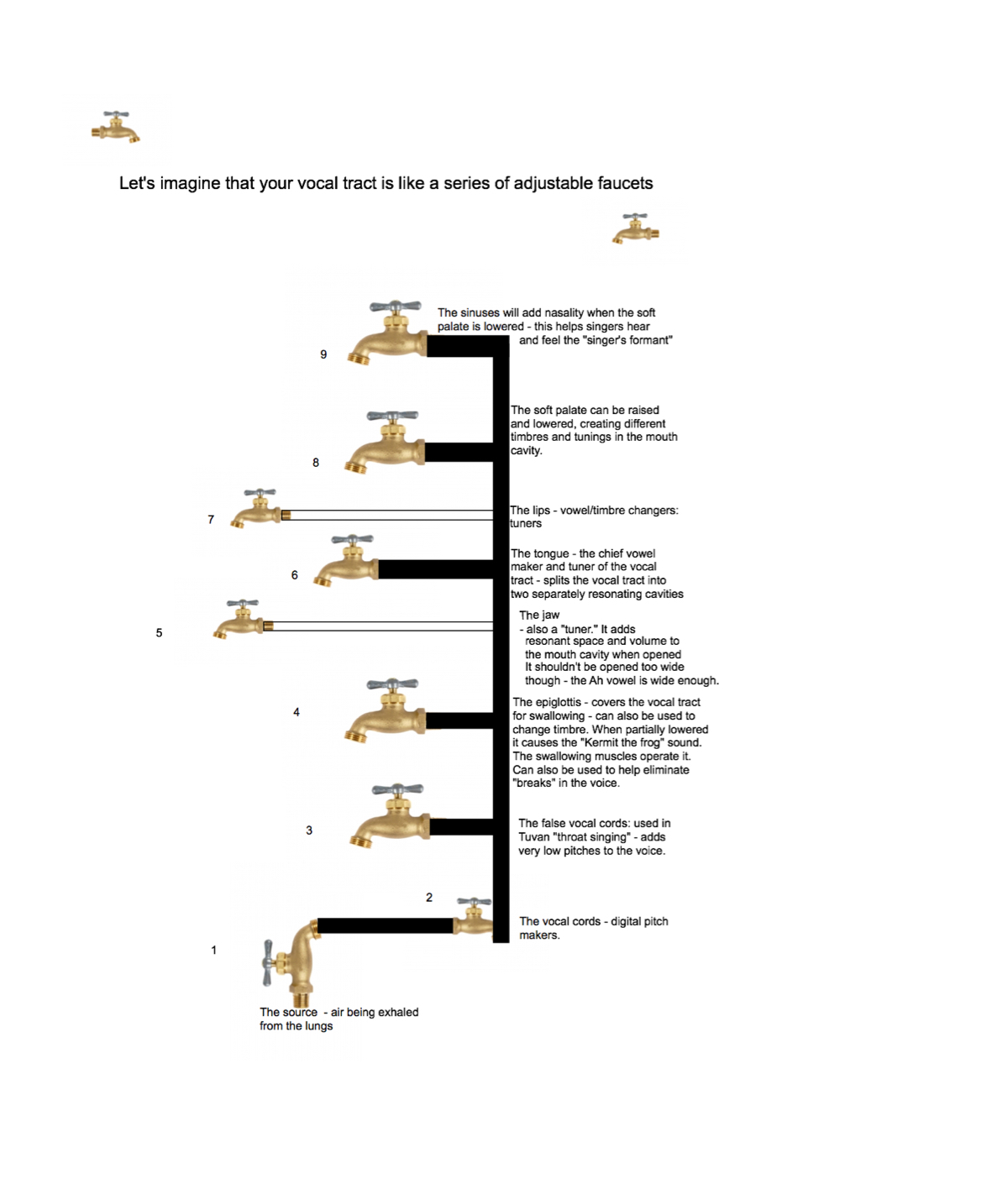

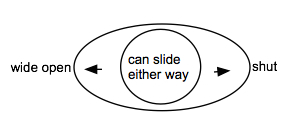

Each

faucet can be “turned on” more or less, creating a great variety of sonic

events. If the water pressure (in the case of singing, it's air pressure)

is strong, each faucet will have some water coming out of it. This pretty

much is the way singers “work” the air flowing through their vocal tracts

and out into a room, auditorium or a microphone. We will examine each

“faucet” to see how it works, and how it affects singing

technique.<br><br> Remember, it is through the control of the

flow of air through “containers” of varying and changing sizes that a

singer exercises his or her technique(s).Most writings about voice

production begin with a chapter about breathing. Generally speaking, a

singer needs to inhale enough breath to sing the next phrase. The

diaphragm is what sucks the air into the lungs. It is only an organ of

inspiration (breathing in). The minute it stops breathing in, it relaxes.

You do NOT sing with the diaphragm! Your several sets of abdominal muscles

are responsible for your singing, speaking, blowing up balloons, etc. You

breathe in with the diaphragm.We are concerned here with how you use the

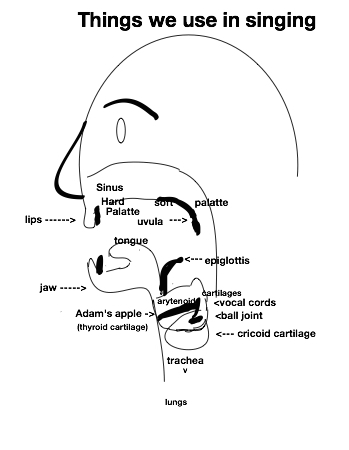

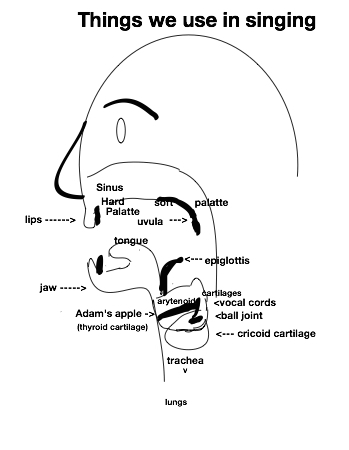

air you inhaled into your lungs.Let's take a look at some of the things in

your body which do some of the work when you sing.<br> <img

alt=">

Each

faucet can be “turned on” more or less, creating a great variety of sonic

events. If the water pressure (in the case of singing, it's air pressure)

is strong, each faucet will have some water coming out of it. This pretty

much is the way singers “work” the air flowing through their vocal tracts

and out into a room, auditorium or a microphone. We will examine each

“faucet” to see how it works, and how it affects singing

technique.<br><br> Remember, it is through the control of the

flow of air through “containers” of varying and changing sizes that a

singer exercises his or her technique(s).Most writings about voice

production begin with a chapter about breathing. Generally speaking, a

singer needs to inhale enough breath to sing the next phrase. The

diaphragm is what sucks the air into the lungs. It is only an organ of

inspiration (breathing in). The minute it stops breathing in, it relaxes.

You do NOT sing with the diaphragm! Your several sets of abdominal muscles

are responsible for your singing, speaking, blowing up balloons, etc. You

breathe in with the diaphragm.We are concerned here with how you use the

air you inhaled into your lungs.Let's take a look at some of the things in

your body which do some of the work when you sing.<br> <img

alt=">

When you take a deep breath, you squish your liver and your stomach and

all that soft tissue in a downward direction. Your belly will usually

expand. If you expand your ribcage when inhaling, your stomach won't bulge

out as much. That always looks better. If you notice where the sternum is

above (it's your breastbone) and you elevate that, your ribcage will

expand, your posture will improve, and you will look marvelous. You may

also find yourself getting a better breath when inhaling. Once you have

inhaled, your diaphragm relaxes and your “abs” take on the job of

exhaling, speaking, singing, yelling, etc. If you are speaking, singing or

yelling, your vocal cords go to work as well, providing you with the first

“faucet” with which to squeeze the air being pumped against them from your

lungs. Your abs are the generators of the squeezing of your intestines,

stomach, liver, etc. They get pushed into your relaxed diaphragm, and your

diaphragm gets squeezed up against your lungs.

Faucet #2.

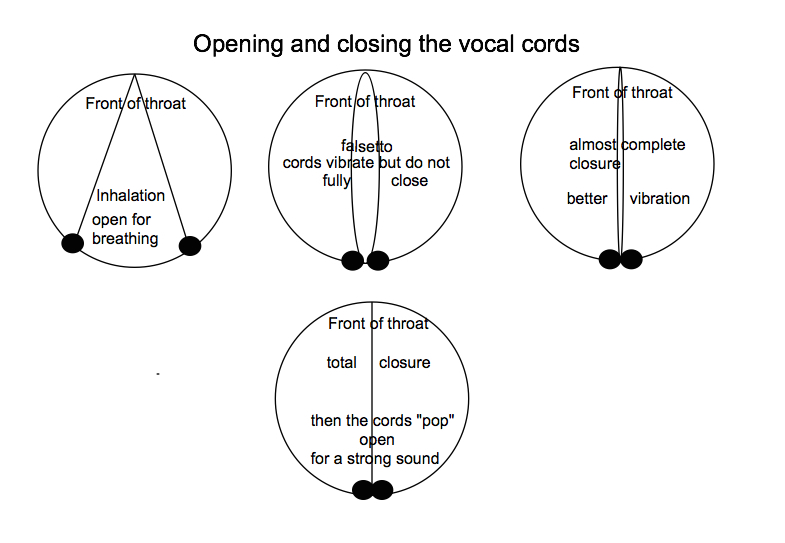

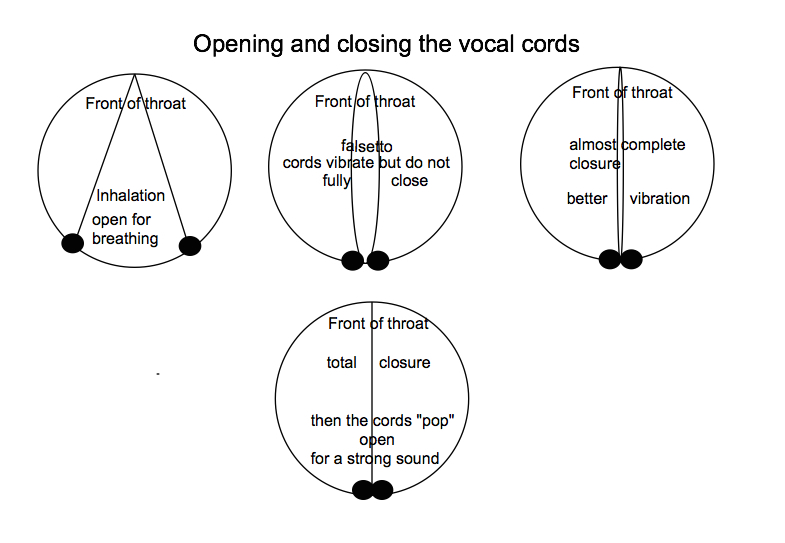

If you have left your vocal cords apart (as when you breathed in) then

that first faucet is entirely open, and creates no resistance to the flow

of air.... you simply exhale. However, if your vocal cords are brought

together and held there, you will be making some sort of sound. This means

the you have adjusted the first faucet, creating some resistance to the

flow of air. Since the vocal cords get pulled together, they begin to

vibrate as the air passes through them. You can make your lips vibrate

almost the same way (they used to call it a “rasberry”). If you add a

resonator by putting your lips in a trombone or tuba mouthpiece, you can

make pitches similar to the way your vocal cords make pitches in your

vocal tract. You can feel the resistance your lips need to make a

“rasberry.” The same is true for the vocal cords. To make pitches, they

vibrate, causing you to feel some resistance in your throat – not a lot

unless your are yelling.

At this point, you might feel some “synergy” between your abs and your

vocal cords – or, you may not. This can prove to be very vexing for some

students as they attempt to understand the concept of what singers call

“support.” More about that in a while.

Faucet #3.

The next faucet is not used too often by “normal” singers. This faucet

represents the false vocal cords, used by Mongolian singers and Tibetan

monks. These false vocal cords allow one to produce very low sounds in the

voice, as they vibrate along with the vocal cords, but usually an octave

or more below the pitch being sung. It is possible to actually sing two

real pitches at the same time, and even add higher harmonic overtones

above, creating three pitches at the same time. The techniques for using

the false cords can be found on line, but it is better to have a teacher,

as these exercises can be rough on the vocal cords themselves if done to

excess or improperly. These false vocal cords are another pair of “air

squeezers,” adding to the compression of the air flowing in the vocal

tract.

Faucet #4.

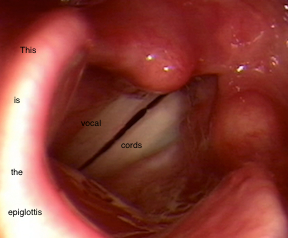

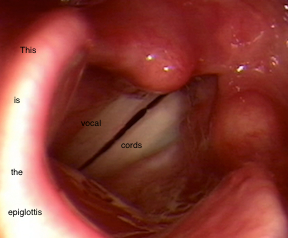

Above the false vocal cords is the next faucet – the epiglottis. This

organ can be raised or lowered or turned into a small tube surrounding the

vocal cords (ventriloquists use this trick to “throw” their voices). It is

operated by a group of constrictor muscles that go to work when we

swallow. When lowered over the vocal cords while singing, a “Kermit the

frog” or “Pee Wee Herman” sound is produced.

![]()

Faucet #5.

The jaw in singing is most often used as a tuner of both vowels and an

adjuster of vocal “color” or timbre (pronounced tamber – originally a

French word). Choral

directors often direct singers to “drop the jaw” which usually results in

the singers opening the mouth too wide and loosing the very quality the

director was attempting to achieve. The jaw has a sinovial joint –

basically a ball joint in an elliptical holder.

Choral

directors often direct singers to “drop the jaw” which usually results in

the singers opening the mouth too wide and loosing the very quality the

director was attempting to achieve. The jaw has a sinovial joint –

basically a ball joint in an elliptical holder. Generally,

for singing (and the comfort of the singer) the vowel AH in most people

opens the jaw as far as it needs to open for singing – even for high

notes. The “tenor” in the picture is opening more than he needs to! The

wider the mouth is open, the less resonance there is in the mouth cavity.

In this case, the mouth is serving as a sort of megaphone, rather than a

“tuner.” We will explore the tuning concept of each of these “faucets” in

a much more comprehensive manner a bit later. For now we just need to know

that the jaw serves both vowel and timbre.

Generally,

for singing (and the comfort of the singer) the vowel AH in most people

opens the jaw as far as it needs to open for singing – even for high

notes. The “tenor” in the picture is opening more than he needs to! The

wider the mouth is open, the less resonance there is in the mouth cavity.

In this case, the mouth is serving as a sort of megaphone, rather than a

“tuner.” We will explore the tuning concept of each of these “faucets” in

a much more comprehensive manner a bit later. For now we just need to know

that the jaw serves both vowel and timbre.

Faucet

#6.

This

is the big one! The tongue is probably the most important organ in the

vocal tract – especially for singing. It is often a blessing and a curse

for singer and teacher alike. Sometimes it seems the tongue simply has a

mind of its own and will not do what is asked for. This is often a

teaching problem, as it is very difficult to “train” the tongue to do

things it is not used to doing.There is a way, however, to get that

obstreperous item to do your bidding. It is learning to literally tune the

vocal tract. Not the pitches you are singing, but the vocal tract

itself!Let's examine how the tongue makes two separate cavities in the

vocal tract.

This

is the big one! The tongue is probably the most important organ in the

vocal tract – especially for singing. It is often a blessing and a curse

for singer and teacher alike. Sometimes it seems the tongue simply has a

mind of its own and will not do what is asked for. This is often a

teaching problem, as it is very difficult to “train” the tongue to do

things it is not used to doing.There is a way, however, to get that

obstreperous item to do your bidding. It is learning to literally tune the

vocal tract. Not the pitches you are singing, but the vocal tract

itself!Let's examine how the tongue makes two separate cavities in the

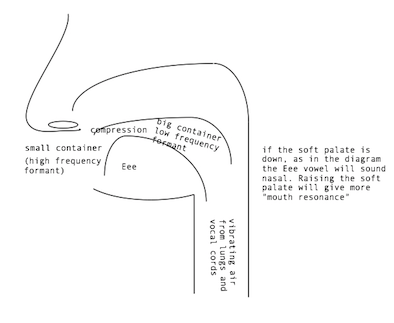

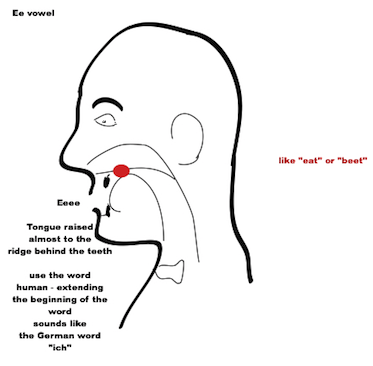

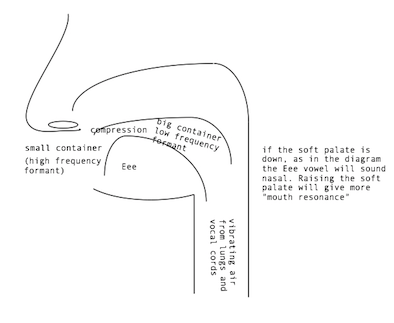

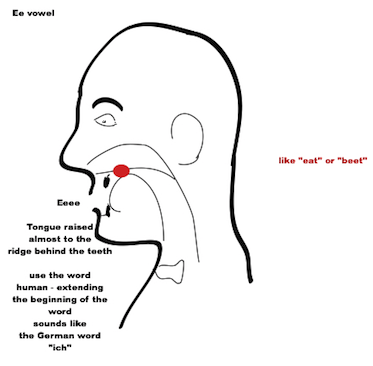

vocal tract. Notice

the

Eee vowel brings the front part of the tongue up and forward, making a

very small cavity in the front of the vocal tract and a large one behind

the “hump” of the tongue. The beginning of the word “human” creates this

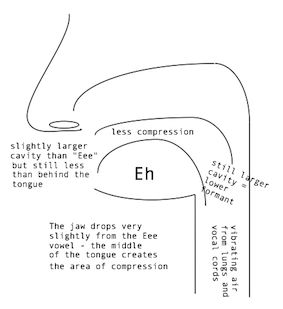

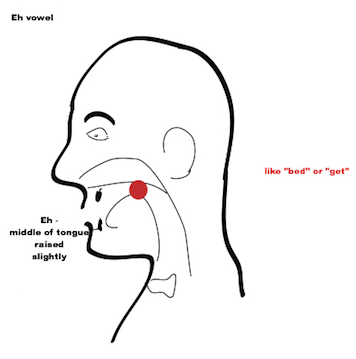

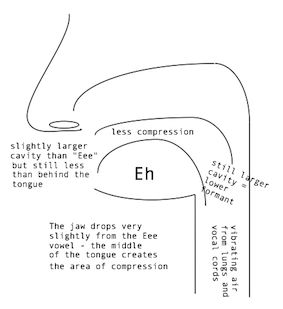

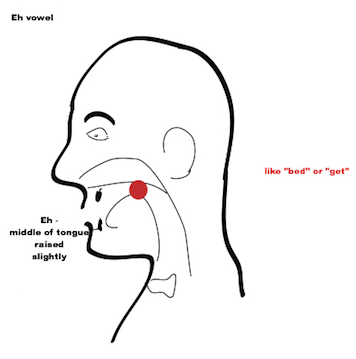

tongue position, as does the German word “ich.”The Eh vowel has the hump

in the middle - you can use the “K” in the word “kick” to feel this tongue

position.

Notice

the

Eee vowel brings the front part of the tongue up and forward, making a

very small cavity in the front of the vocal tract and a large one behind

the “hump” of the tongue. The beginning of the word “human” creates this

tongue position, as does the German word “ich.”The Eh vowel has the hump

in the middle - you can use the “K” in the word “kick” to feel this tongue

position. The

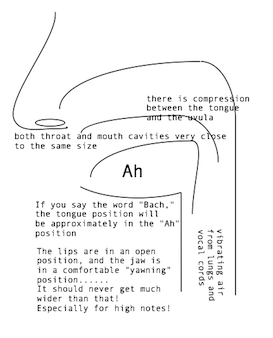

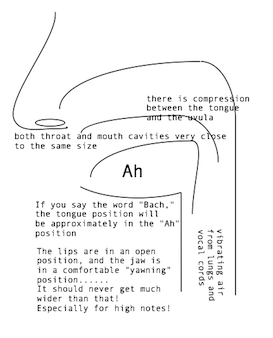

Ah vowel position can be found by saying “Bach” and extending the sound of

the “ch.”

The

Ah vowel position can be found by saying “Bach” and extending the sound of

the “ch.” Wherever

the

tongue is near the roof of the mouth it creates some compression. You

might like to think of that as if we had put a short hose with a nozzle on

faucet #6. You can feel the compression on the roof of your mouth for each

of the three vowels: especially on “human” and “Bach.” It's as though you

were aiming a stream of air (from the nozzle effect) at a specific place

on your hard or soft palate. This is the beginning of your understanding

of vocal technique. Not only can you feel that jet of air, but you can

repeatedly do it by yourself again and again without a teacher. You are

learning the concept of “placement.”By moving your tongue into these

repeatable positions, you are training yourself to get a tactile sense of

what the airflow inside the

Wherever

the

tongue is near the roof of the mouth it creates some compression. You

might like to think of that as if we had put a short hose with a nozzle on

faucet #6. You can feel the compression on the roof of your mouth for each

of the three vowels: especially on “human” and “Bach.” It's as though you

were aiming a stream of air (from the nozzle effect) at a specific place

on your hard or soft palate. This is the beginning of your understanding

of vocal technique. Not only can you feel that jet of air, but you can

repeatedly do it by yourself again and again without a teacher. You are

learning the concept of “placement.”By moving your tongue into these

repeatable positions, you are training yourself to get a tactile sense of

what the airflow inside the

vocal

tract feels like to you. This is very important!

This

is the Eee vowel

This

is the Eh vowel

The

picture

on the next page represents the Aaa vowel (as

in

the word bad, hat , sat, etc)

Here

the mouth works more like a megaphone – this is often a “nasty” sound,

generating a lot of high frequencies. Sounds like Jerry Lewis, The Nanny,

or the Aflac duck. A very useful training sound, often found in r and b

singing and in some Eastern European singing styles (Bulgarian Women's

Choirs).

Here

the mouth works more like a megaphone – this is often a “nasty” sound,

generating a lot of high frequencies. Sounds like Jerry Lewis, The Nanny,

or the Aflac duck. A very useful training sound, often found in r and b

singing and in some Eastern European singing styles (Bulgarian Women's

Choirs).

Faucets

Faucets

Faucets

Faucets

Choral

directors often direct singers to “drop the jaw” which usually results in

the singers opening the mouth too wide and loosing the very quality the

director was attempting to achieve. The jaw has a sinovial joint –

basically a ball joint in an elliptical holder.

Choral

directors often direct singers to “drop the jaw” which usually results in

the singers opening the mouth too wide and loosing the very quality the

director was attempting to achieve. The jaw has a sinovial joint –

basically a ball joint in an elliptical holder. Generally,

for singing (and the comfort of the singer) the vowel AH in most people

opens the jaw as far as it needs to open for singing – even for high

notes. The “tenor” in the picture is opening more than he needs to! The

wider the mouth is open, the less resonance there is in the mouth cavity.

In this case, the mouth is serving as a sort of megaphone, rather than a

“tuner.” We will explore the tuning concept of each of these “faucets” in

a much more comprehensive manner a bit later. For now we just need to know

that the jaw serves both vowel and timbre.

Generally,

for singing (and the comfort of the singer) the vowel AH in most people

opens the jaw as far as it needs to open for singing – even for high

notes. The “tenor” in the picture is opening more than he needs to! The

wider the mouth is open, the less resonance there is in the mouth cavity.

In this case, the mouth is serving as a sort of megaphone, rather than a

“tuner.” We will explore the tuning concept of each of these “faucets” in

a much more comprehensive manner a bit later. For now we just need to know

that the jaw serves both vowel and timbre.  This

is the big one! The tongue is probably the most important organ in the

vocal tract – especially for singing. It is often a blessing and a curse

for singer and teacher alike. Sometimes it seems the tongue simply has a

mind of its own and will not do what is asked for. This is often a

teaching problem, as it is very difficult to “train” the tongue to do

things it is not used to doing.There is a way, however, to get that

obstreperous item to do your bidding. It is learning to literally tune the

vocal tract. Not the pitches you are singing, but the vocal tract

itself!Let's examine how the tongue makes two separate cavities in the

vocal tract.

This

is the big one! The tongue is probably the most important organ in the

vocal tract – especially for singing. It is often a blessing and a curse

for singer and teacher alike. Sometimes it seems the tongue simply has a

mind of its own and will not do what is asked for. This is often a

teaching problem, as it is very difficult to “train” the tongue to do

things it is not used to doing.There is a way, however, to get that

obstreperous item to do your bidding. It is learning to literally tune the

vocal tract. Not the pitches you are singing, but the vocal tract

itself!Let's examine how the tongue makes two separate cavities in the

vocal tract. Notice

the

Eee vowel brings the front part of the tongue up and forward, making a

very small cavity in the front of the vocal tract and a large one behind

the “hump” of the tongue. The beginning of the word “human” creates this

tongue position, as does the German word “ich.”The Eh vowel has the hump

in the middle - you can use the “K” in the word “kick” to feel this tongue

position.

Notice

the

Eee vowel brings the front part of the tongue up and forward, making a

very small cavity in the front of the vocal tract and a large one behind

the “hump” of the tongue. The beginning of the word “human” creates this

tongue position, as does the German word “ich.”The Eh vowel has the hump

in the middle - you can use the “K” in the word “kick” to feel this tongue

position. The

Ah vowel position can be found by saying “Bach” and extending the sound of

the “ch.”

The

Ah vowel position can be found by saying “Bach” and extending the sound of

the “ch.” Wherever

the

tongue is near the roof of the mouth it creates some compression. You

might like to think of that as if we had put a short hose with a nozzle on

faucet #6. You can feel the compression on the roof of your mouth for each

of the three vowels: especially on “human” and “Bach.” It's as though you

were aiming a stream of air (from the nozzle effect) at a specific place

on your hard or soft palate. This is the beginning of your understanding

of vocal technique. Not only can you feel that jet of air, but you can

repeatedly do it by yourself again and again without a teacher. You are

learning the concept of “placement.”By moving your tongue into these

repeatable positions, you are training yourself to get a tactile sense of

what the airflow inside the

Wherever

the

tongue is near the roof of the mouth it creates some compression. You

might like to think of that as if we had put a short hose with a nozzle on

faucet #6. You can feel the compression on the roof of your mouth for each

of the three vowels: especially on “human” and “Bach.” It's as though you

were aiming a stream of air (from the nozzle effect) at a specific place

on your hard or soft palate. This is the beginning of your understanding

of vocal technique. Not only can you feel that jet of air, but you can

repeatedly do it by yourself again and again without a teacher. You are

learning the concept of “placement.”By moving your tongue into these

repeatable positions, you are training yourself to get a tactile sense of

what the airflow inside the

Here

the mouth works more like a megaphone – this is often a “nasty” sound,

generating a lot of high frequencies. Sounds like Jerry Lewis, The Nanny,

or the Aflac duck. A very useful training sound, often found in r and b

singing and in some Eastern European singing styles (Bulgarian Women's

Choirs).

Here

the mouth works more like a megaphone – this is often a “nasty” sound,

generating a lot of high frequencies. Sounds like Jerry Lewis, The Nanny,

or the Aflac duck. A very useful training sound, often found in r and b

singing and in some Eastern European singing styles (Bulgarian Women's

Choirs).