See-Saw-So

Sight Singing System

A sight system that makes sense!

The systems we use to teach sight singing are

often more confusing than valuable. We hang on

to these old systems because they do work. As

a performing musician, songwriter, singer and

teacher for over fifty years, I have noticed

that sight singing has a learning curve that

is long and difficult. With so many variations

many music students just "give up" this

valuable tool before they become fluent in its

use.

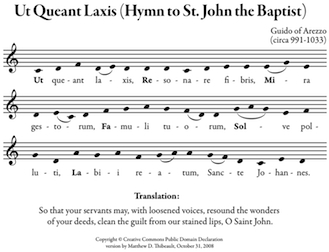

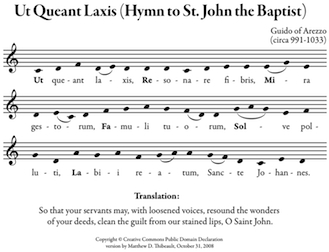

Most Americans discard solfeggio before they

actually learn it, because it is full of

inconsistencies. Besides, it was invented by

Guido D'Arezzo in the eleventh century using a

section of Gregorian Chant which, over a

course of about three years, taught singers

and others a syllable system for note-reading.

It also taught good recognition of interval

relationships.

It used only six notes, not eight, as in our

diatonic systems

This was fine for monks in the abbey singing

praise to St. John, but for contemporary

learners of music, there are problems.

First of all, how do you sing sharps and flats

in a way you always know what's sharp and /or

what's flat?

The system widely used in Europe becomes "do,

di , re, ri, mi" - there is an inconsistency

at this point, because the ee sound used

between steps three and four and seven and

eight (e and f, and b and c in the key of C

major) (indicating half steps) now has to be

changed to a different vowel between the notes

e# and F#.......

In Guido's time, the note e# wasn't yet a note

in any of the scales that were used.

Guido used only a six note hexachord system

which was perfect for Gregorian chant, but

much too limited for today's musician. As a

consequence, changes were made, adding new

syllables and notes to fit the "full" diatonic

system.

Instead of: Ut, re, mi, fa, so - it became Do,

re, mi, fa, so, la, si, do (and once again,

another change, in order to avoid two "s"

sounds, si became (in some countries) ti (with

jam and bread).

All these additions and changes never

addressed the original inconsistencies of

Guido's system "if it was good enough for our

fathers and grandfathers so it must good

enough for you" syndrome.

For Guido's musicians there were no

inconsistencies because written music was

brand new and his system had no predecessors.

Using the chant is fine but somewhat confusing

for new students: it is in Latin, and

meaningless to those unfamiliar with that

language.

Beginners in music usually know the names of

the notes. In America this is generally true.

As a consequence the system I have worked out

is totally consistent for those students.

It uses what's already known (the names of the

notes) and that doesn't change for any note

name: "c" always has the sound of "see."

I noticed that in the scale, almost all notes

had the "ee" vowel present. The only

exceptions were "f" and "a."

The next steps were easy. Sharps and double

sharps would use different vowels:

flats and double flats would use the others.

Everything sharp would sound like "AH" and

everything double-sharped would sould like

"EH."

What about the note "A"?

When sharped, it simply becomes "AH" and

likewise, when sharped, the note "E" becomes

"ee-ah" or more familiarly, "yah" (double

sharped = "yeah").

The flats behave in the same manner. All flat

notes become "OH" sounding. All double flats

become "OO" sounding. Once again, a flat

becomes "oh," a double flat becomes "oo."

E flat becomes "yo" and e double flat becomes

"you." The only discrepancy is in spelling and

pronunciation of the note "G#." Spelled, it

looks like "gah - it should be pronounced with

the sound of "jaw" "jeh" "jo" and "joo."

The only other helpful suggestion in

performing these syllables is to use a slight

glottal stop between "g sharp" ("jaw") and "A

sharp" "ah."

Normally, "gee"- "ay" sings smoothly and

understandably, but "jaw-ah" "jeh-eh" "jo-oh"

and "joo-oo" need that small separation.

We do this naturally between the note "d" and

"e." (example - say "abcde") That little

separation is called a glottal stop.

When you hear an "AH" vowel, the note is

sharped, and only a single syllable is needed.

When you hear an "OH" vowel, the note is

flatted, and only a single syllable is needed.

No need to sing "e sharp" on a sixteenth note

or an inconsistent vowel sound as needed in

solfeggio.

If the note is c# the sound is "Sah,"

if it is c-flat, the sound is "So" -

the name of this sight-singing system becomes

the sounds for the notes "C" "C #" and "C

flat."

See - Saw - So.

This system can be used with a moveable "Do"

as well

(why anyone would want to do so with this

system is beyond me)

but works best with a "Fixed Do." ("Do" being

the note "c")

An additional feature is the use of colors:

Sharp note = red,

Double sharp notes =

orange,

"Regular" notes =

black,

Flat notes = blue,

Double flat notes

= green

This additional

feature is good for those who are

visual, rather than auditory

learners.

One other feature which might go

unnoticed: students learn key

signatures by default - since

singing any scale with the correct

notes in this system requires

singing the sharp and/or flat

vowel sounds, the student becomes

aware of the number of sharps or

flats to be sung in the "correct"

scale:

for example E Major: ee, fah,

jaw, ay,

bee, saw,

dah,ee - The

four "ah sounding"

note/syllables are

sharps.

Whenever it sounds

"ah" the note is a

sharp.

How many sharps in the

key of "E"?

Try it for yourself

and see if it doesn't

make complete sense.

I am aware I have

re-invented the wheel,

but I think I've

outfitted it with a

wonderful new set of

tires

which run more

smoothly and last for

a lifetime!

Or, to quote another

another cliche - a

better mousetrap.

Exercises

and examples:

See

Saw So Video 1

The

Ear Train - pg.1

The

Ear Train - pg.2

The

Ear Train - pg.3

Exercises

- #1

Tetrachords

Tetrachord

Exercises

Indian

system (Carnatic) Sa, re, ga, ma, pa, da,

ni, sa - videos to study

Indian

system (Carnatic) Sa, re, ga, ma, pa, da,

ni, sa - videos to study

Indian

system (Carnatic) Sa, re, ga, ma, pa, da,

ni, sa - videos to study

Indian

system (Carnatic) Sa, re, ga, ma, pa, da,

ni, sa - videos to study

SeeSawSoClefs

Transposition

- learning how to do it

Folk

Songs

These will help you to learn patterns of

intervals and scales in different melodies and

keys

He's

Gone Away Gone Away

Black,

Black, Black Black, Black

Ba,Ba

Blacksheep Blacksheep

Danny

Boy

The

Campbells Are Coming

Chester

Clementine

Silver

Dagger

Beautiful

Dreamer

Froggie

Went a'Courtin'

Buffalo

Gals

Amazing

Grace

Greensleeves

He's

Got The Whole World In His Hands

Hatikvah

All

The Pretty Little Horses

Frere

Jacques

Good

Night Ladies

Aura

Lee

Green

Grow The Lilacs

Cielito

Lindo

Careless

Love

Go

Down Moses

Go

Tell It On The Mountain

Hava

Nagila

All

Through The Night

On

The Banks of the Ohio

Deep

River

Down

By The Riverside

Comin'

Through The Rye

What

Do We Do With A Drunken Sailor?

Freight

Train

Down

In The Valley

Auld

Lang Zyne

He's

He's